Try to remember Stephen Curry in 2013: before the championships, before the worldwide acclaim, before the podium memes, before he was Steph.

Picture him on this very day five years ago. He was still baby faced, clean shaven but for a little patch covering his chin. His 38 points one night before had been overshadowed by the Miami Heat, the league’s super-team at the time, winning an overtime thriller. At tipoff on Feb. 27, 2013, Curry wasn’t even the biggest storyline of the game — that belonged to a New York Knicks renaissance. Curry stepped onto the court at Madison Square Garden in yellow-and-turquoise Nikes that the national broadcast would highlight later that night, because he had written part of a Bible verse on them: “I can do all things.”

That night, Curry made those words prophetic.

For exactly 48 minutes — he never substituted out of the game — Curry flaunted his revolutionary brand of basketball pushed to its highest apex yet. He flipped up layups at previously undiscovered angles and sunk soft jumpers within the paint. He attempted 13 shots behind the three-point arc and made 11, all steeped in his unwavering confidence.

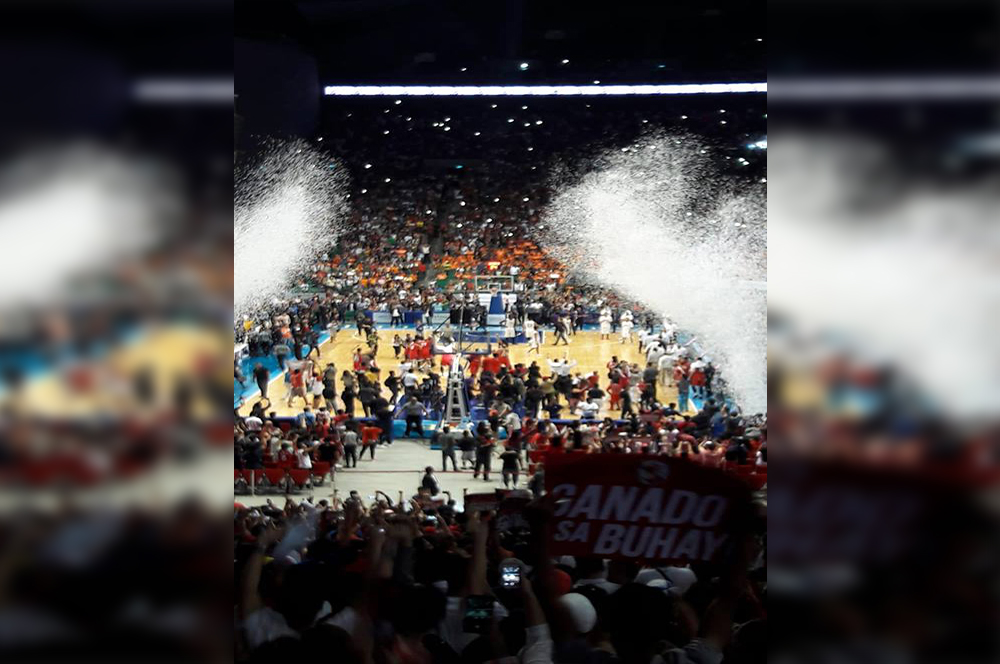

By the time it was over, Curry had scored 54 points, which remains his career high. His game score, a Basketball Reference metric measuring overall contribution, was the highest recorded all season. He became the first ever 50-point scorer to also hit double digit threes.

That moment, on that stage, launched Curry to the front of the NBA’s collective consciousness. He had already been a college sensation and his playing style was magnetic, but Raymond Ridder, longtime Warriors PR lead, still easily recalls the flood of media requests in his inbox the following morning. Curry was still two years removed from his first MVP, but on that evening, he offered a glimpse of what was to come — his own greatness, but also the league-changing revolution he would spark. Stephen Curry was so good that night the Madison Square Garden crowd cheered for him. That’s Harrison Barnes’ distinctive memory from that game when I ask him earlier this season.

“That was my first year, my first time in The Garden,” Barnes says. “Just to see him go electric like that, literally having their fans cheer for us and for Steph on the road.”

The night before, Curry’s 38 points against the Indiana Pacers came in a game that included an on-court brawl that nearly spilled into the stands. If David Lee, the team’s lone All-Star, hadn’t been suspended one game for that, Warriors head coach Mark Jackson probably doesn’t ask Curry to play the whole night against the Knicks.

“When Steph’s having that kind of volume night, you know he’s going to go for a lot,” says Bob Fitzgerald, the Warriors play-by-play announcer since 1993. “They just never took him off the floor.” No one on New York’s roster was equipped to handle a fully functioning Curry. Everyone was torched, but the brunt of the onslaught fell on Raymond Felton.

“He had an unbelievable night,” Felton says. “The basket was as big as the ocean for him.”

Curry was actually quiet in the first quarter, but that was just the calm before the storm. In one moment halfway through the second quarter, he slowed from a near sprint and launched a transition triple despite having a three-on-two break. In another, he challenged reigning Defensive Player of the Year Tyson Chandler with a high-arcing floater that drifted over his outstretched hands. His 23-point second quarter sent him into the half with 27.

He came out just as hot in the third.

“All of a sudden you see the points creep up, you know, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35,” Barnes says. “The mood in the arena was different. It’s not just like, ‘This guy’s hot right now.’ It’s like, ‘Something big is happening.’”

No play exhibited that more than another transition three-pointer launched even with teammates running with him. With 4:43 left in the fourth and a two-point deficit, Curry snatched the ball, crossed half court, and immediately started lining up a shot that the entire building could see coming. Felton leapt at him. It didn’t matter. Curry hit from 25 feet, just right of dead center.

Knicks coach Mike Woodson attempted to collect his team with a timeout afterwards, and Curry shimmied his shoulders and yelled up into the crowd the whole way back down the court. It was his 46th point. He had earned the right to celebrate.

Yet, Woodson’s timeout worked. In retrospect, the game had so many oddities: That Lee’s absence cleared the path for Draymond Green’s first and only start his rookie year; that ESPN highlighted the Nike shoes, still one year removed from Curry joining Under Armour and another from becoming its most recognizable sponsor; that Chandler grabbed 28 rebounds for New York, something he instantly remembered when I brought up that game while recalling nothing else.

The weirdest, though, remains the final result: The Knicks went toe-to-toe with Curry’s best night ever and won anyway.

Oh, Felton damn sure remembers that: “I blocked his shot twice to win the game. Fifty-four points, but I got the stops to win.” (The play-by-play only shows one block, Raymond, but your point remains.)

But even Felton’s teammate Jason Kidd, five years removed from starting that game, remembers Curry’s performance while forgetting the actual result.

“I think we had a chance to win that game,” Kidd says.

I tell him the Knicks actually won.

“So we did the right thing,” he laughs. “The game plan was to let him score.” Draymond Green remembers even less than Kidd. Yes, he started, and yes, he played 27 minutes, but when I ask him about it at a shootaround last November, Green stares blankly.

“You remember this game?” he asks Shaun Livingston, seated next to him, who provides no help. Green racks his brain again, and then admits defeat.

I ask the same question to J.R. Smith, who scored 27 points that evening for New York, and he also demurs. The game might have stood out to fans, to national media, to the announcers present, and even to Harrison Barnes, witnessing a Curry supernova in his first trip to The Garden. It clearly didn’t register the same way with players.

“I don’t think Steph was quite Steph at the national or world level that season at all,” Fitzgerald says. That postseason, the Warriors beat the Denver Nuggets and put the league on edge when they challenged the San Antonio Spurs. Curry, in particular, starred in those two series. For Barnes, that’s when he realized what heights Curry could reach.

“No one could guard him,” Barnes recalls. “Seeing him get to that point, that was really the opening of realizing how good this guy could be, (that) he can be the best in the league.” Doris Burke distinctly remembers not wanting to leave the building. Around this time of year, matchups often blend together for media. They turn into something that is part routine, part exhaustion — an inevitability of constant cross-country travel. In Burke’s words, it takes “something special to wake you up” from that. Something like that Wednesday night.

“As announcers, we know when either an individual performance or a game has been great, because when we leave the arena, the announce team generally doesn’t want to leave each other,” Burke tells SB Nation.

What they felt compelled to talk about over drinks in an evening they didn’t want to end was Curry, of course. Burke had covered Curry’s games at Davidson and throughout his first four years in the league. On that evening, she saw something different from him.

“I remember watching Steph for what I felt was the first time be physically demonstrative in reaction to his own play,” Burke says. “I remember an energy coming into play and having the sense that night that there was a sense of wonder for him.”

That sense of wonder was apparent that night. What wasn’t apparent, at least not right away, was how far Curry’s career could go.

No one would have expected Curry’s career rise when he arrived in the league. He began at Davidson as a slightly-built player’s son, exploded as a national mid-major star, blossomed into a sensational young NBA shooter, and finally peaked to nearly everyone’s surprise as the league’s first-ever unanimous MVP. Looking back, despite his barely there facial hair, we can see that player on the court against New York scoring 54 points in the same way he does it today. In that moment, though, despite how special the night was, his future was hard to predict.

“I don’t know if I would have ever thought, even in the aftermath of that game, that this is going to be a two-time MVP,” Burke says. “Never did I think that he would consistently, night after night after night, get to that point.”

And as Fitzgerald notes: “You’re talking about the best human being to ever shoot a basketball in the history of the world. So if you could have anticipated that when you saw that little baby-faced kid at Davidson, then you’re pretty prescient.”

This is the problem that Curry presented us five years ago: How can you predict something that you’ve never seen before? Curry was a new archetype.

“It never crossed my mind that this individual would basically change the definition of what is and is not a quality shot in the NBA,” Burke says. “And having listened to Steve Kerr in those coaching meetings that we are fortunate to sit in pregame, where he talks so eloquently about how much Steph changes an opponent defensive schemes, how much further out they’re forced to contend, how that shape-shifts the defensive layout of the floor, it’s incredible.”

Longtime Davidson College head coach Bob McKillop watched Curry light up New York on a bus ride back to Davidson, North Carolina.

“We had just had a victory against Elon at Elon, so on the bus ride home from the game, we were watching,” McKillop said. “It created quite a bit of joy and exhilaration, not just coaches but our entire team. Our entire team was glued to the set.”

McKillop was thrilled, but he was hardly surprised by what he saw: Curry had always risen to the biggest stage, first at Davidson and now professionally. McKillop never doubted Curry’s ability to reach his peak, even if he didn’t know it would be quite this high. And that word, peak, was a problem for McKillop and the Davidson staff. Every time that Curry reached one peak, he would climb towards another.

“When he would hit consecutive threes against somebody, we would look at the bench and say, ‘Don’t you know that’s Steph Curry?’” McKillop says. “He never ever reached what we thought was his highest level, because each time he stepped on the court he’d reach another level.”

In the five years since scoring 54 points in The Garden, Stephen Curry has won two championships, two MVPs, shattered three-point records, led the Warriors to the greatest regular season of all time, and has generally asserted himself as the most genre-defining, game-shifting player that we’ve seen in, well, decades.

No one saw this coming — not Doris Burke, not Bob McKillop, not you, not me, probably not even Stephen Curry himself. In retrospect, we never could have.

The Golden State Warriors have a running, organization-wide joke, but it also doubles as an ethos. It started with team president Rick Welts, but it has now caught on with everyone. When someone asks if Stephen Curry is really that good — and trust me, they ask — then they always reply like this.

“No,” they say. “He’s better.”